As a leader driving change, you will encounter resistance.

In a survey conducted by the Lean Enterprise Institute, respondents overwhelmingly listed resistance as the biggest obstacle to implementing and sustaining Lean.1 Three of the top four obstacles listed were middle management resistance, employee resistance, and supervisor resistance. In short—resistance.

Why are people so resistant to Lean? After all, Lean can reduce costs, improve quality and customer satisfaction, and even make work easier and safer. And when resistance does show up, why are people so thrown by it?

Resistance is not an obstacle to Lean implementation; it’s a predictable consequence of it.

Here’s what you’ll find in this article:

- Resistance is normal. It’s what happens when you try to change anything.

- How to plan for resistance. It’s going to happen, so be ready for it.

- How to manage group resistance and use it to your advantage. If you don’t manage resistance, it manages you.

1. Resistance is normal

Resistance is a normal response to change. However, how you manage resistance can slow progress—even bring it to a dead stop—or it can be a phase you pass through on your way to Lean excellence.

Everyone is resistant to change at some level. I am; you are; everyone is. Think about some change that you’ve been meaning to make. Maybe it’s that exercise or diet program you’re on (or want to be on). You may want to eat well and exercise regularly, but there are times when you don’t, even though you know it’s the right thing to do. When you accept resistance as normal, then it becomes easier to deal with. There is nothing inherently wrong with resistance. It’s a matter of perspective: one person’s resistance is another person’s “taking a stand.”

The key issue in resistance to Lean is change, not the ideas of Lean. What is perceived as resistance to Lean may in significant part be a simple, run-of-the-mill resistance to change.

I’ve conducted interviews of employees undergoing a Lean transformation at a particular service organization. They say they like the idea of Lean; to some degree Lean makes sense to them. What they don’t understand is how it applies in their organization and their type of business. They don’t understand how a methodology, which appears to have come from the automobile industry, might have a positive impact on what they do in a service delivery profession.

Are they being resistant to Lean? Maybe. Maybe not. Most likely they really don’t understand how Lean applies to them. If that is the case, but they’re being treated as “resistant,” then the issues that they’re concerned with are not being addressed. The fact is that whatever kind of change you implement, people are likely to be resistant—on some level—to the change. It has more to do with how people react to change, not with Lean.

Resistance will happen. Why? Let’s start with two key principles we can count on:

- Every action causes a reaction.

- Change asks people to move outside of their comfort zone.

When you cause a change in an organization, people react at a magnitude more-or-less equal to the magnitude of the change. Newton’s Third Law states that for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. A big change will get a big reaction, and a small change a small reaction.2 Lean can be a big change for some (with the benefits to match).

Change asks people to move outside their comfort zone. Most have an understanding of the term “comfort zone;” here is how I am using it, and why it’s relevant to resistance to Lean.

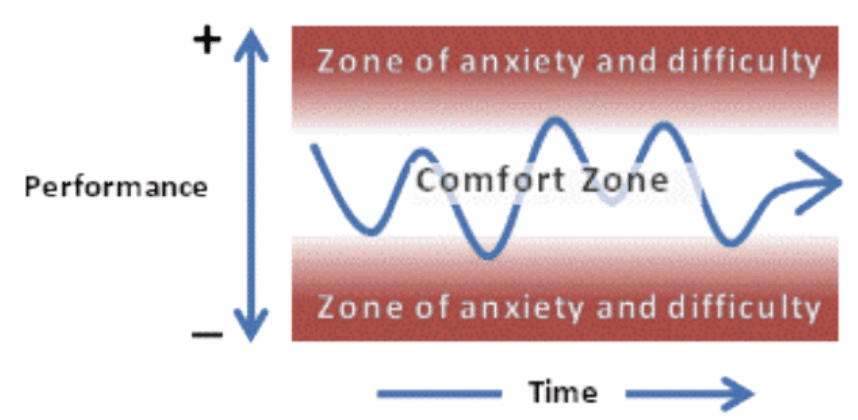

The comfort zone is a zone of performance bounded by upper and lower limits that are determined by a person’s or group’s anxiety and capability.3 Referring to the chart below, there is a somewhat stable range within which people are comfortable performing. When functioning either above or below this normal range of functioning, individuals and groups often experience emotional anxiety and functional difficulty. As performance increases or decreases beyond a certain point, anxiety and/or the level of difficulty bring performance back into the comfort zone.4

The comfort zone is where people work day in and day out. Everyone—even high-performers—function within their own comfort zone. This is where habit has worn a groove into their routine.

When individuals or groups are challenged to change how they do things to improve their performance, they may experience emotional anxiety or functional difficulty. They wonder, “can we do it?” “Is it possible?” “If we can’t do it, what will happen to us?”

As biological organisms, we often don’t make the distinction between positive and negative change. What’s most important to us is that we have been cruelly shoved out of our comfort zone and we want to get back into that comfortable groove. It’s a biologically-based urge to do what’s comfortable and avoid negative feedback. Obviously some have a higher threshold for change; some have a lower threshold.

Now that we understand resistance to change is predictable, let’s plan for it.

2. How to plan for resistance

If resistance is normal human behavior, then how can we plan for and manage it?

Help people deal with two key things:

- emotional anxiety

- role clarity

Put structures and processes in place that (1) reduce anxiety (good structures and processes reduce anxiety), and (2) channel resistive behaviors into productive activities.

The structures that reduce anxiety are the following:

- Role definitions and their relevance in the new vision

- Problem solving and suggestion processes5

1. Role Definitions and Their Relevance in the New Vision

People will be more likely to resist change when they are unclear about their role and their relevance in the changed environment. This lack of clarity affects people in two ways. First, if they are unclear about their roles and responsibilities, they will not be able to execute their role. What looks like resistance can actually be honest confusion. Second, people are more likely to move into change if they understand their relevance in the new environment.

I was conducting preparation activities for a workshop in the records management department of a large, multi-national company. The group had nine locations in facilities throughout North America. They were tasked with consolidating their facilities into five locations. I had difficulty getting the team to engage and focus on data collection until we were able to surface their pivotal concern: if they were to reduce the number of physical locations, what would happen to those who worked at the locations to be closed? And what about the future of records management?

These are challenging questions, and one only the sponsor could address. The sponsor met with the preparation team and restated the goals of the upcoming workshop, and re-explained the business challenges that drove the need for the workshop. From there he articulated how records management fit into the future of the organization.

He was also forthcoming with the reality that at some point in the next couple of years, there may be reductions in workforce, but not immediately. Those who worked in facilities that were closed would either work at the facility nearest to them or telecommute.

Once the team understood their place in the future of the company, they were able to begin more productive work.

2. Problem solving and suggestion processes

Set up problem-solving processes to deal with issues that are brought up concerning the change. It is impossible for the planners of any change effort to think of every contingency or consequence. Those contingencies and consequences, whether real or imagined, are a source of resistance and an excuse for not moving forward. Remove that excuse by establishing a simple process to address issues and suggestions. Find a way to involve the stakeholders of the issue or suggestions to be involved in the process.

[see to sidebar 1]

Now that you’ve set up structures that channel resistance into productive activities, you are ready to manage group and individual resistance.

3. How to manage group resistance and use it to your advantage

Don’t resist resistance; manage it.

The best way to increase resistance in your organization is to resist it. It is axiomatic that whatever you resist persists. This goes for resisting resistance. When you resist resistance, you are practicing the very behavior that you are trying to manage in others. In fact, you can amplify their resistance by your own behavior.

How do you not resist resistance and still move forward with your change?

The Resistance Talk Cycle offers a process to manage resistance, and seize opportunities for continuous improvement. You have many opportunities to channel resistance to Lean into productive activities. Below are the steps of the Resistance Talk Cycle.

| Resistance Talk Cycle |

|

1. State your commitment to Lean

This includes your vision, goals, expectations, and so forth. Tell them what you, yourself, will be doing differently as a result of the Lean initiative.

[see sidebar 2]

2. Encourage expression of concerns and issues

Where there is resistance, there is always a concern or issue, whether real or imagined. In either case, you want all issues out on the table so you can deal with them directly. It is useful to think of this step as “data collection.”

3. Repeat back what you hear from individuals; check for understanding

Confirm with the speaker that you heard correctly and understand what is being said; use the speaker’s words when possible. In checking for understanding, you are validating the person. Ask the group if there are others who agree or disagree. Explore the opinions held by those in the group.

4. Use the problem-solving process

If appropriate to the issue or concern, funnel the issue or concern into the problem-solving process outlined above (or one of your own design). If possible, enlist the person (or people) in the process.

Don’t feel compelled to solve all issues or answer all questions on the spot. As the leader, it is not your job to have all the answers or solutions. It is your job to hold the vision, set the strategy and goals, and provide resources. Use the problem-solving process to engage others in the solutions.

5. Restate your commitment to Lean

It is important that the group sees that you are unwavering in the face of resistance. This is what people are looking for, whether they realize it or not. They want to be assured that you mean business with Lean. Also, as you manage yourself in a non-anxious way, by virtue of modeling, you will be helping the group learn to manage its own anxiety about change.

[see sidebar 3]

What you resist persists, so don’t resist resistance.

Resistance is a normal and expected phenomenon of Lean implementation, as it is with any other meaningful change effort. Plan for it. Have processes in place to deal with it. Channel the energy generated by resistance into problem-solving and suggestion processes. These processes can fuel efforts to launch and sustain Lean. That’s the way to get all the benefits of Lean, along with buy-in at every level.

Sidebar 1

Here is a scalable process for managing issues:

When I work with organizations, I capture all issues—whether I believe they are relevant or not. This demonstrates that I’m paying attention to their concerns, and that their issue will be addressed at a more appropriate time.

Of course, different issues require different levels of attention. For important issues that require more immediate attention, I put the issue into one of four categories:

- Parking lot: these issues don’t demand immediate attention, or are not critical

- Go-do’s: these are important issues that are simple enough that one or two people can “go do” it; they typically don’t require much planning or cross-functional coordination

- Project: an issue large or complex enough that it takes a team to resolve it

- Lean workshop: a large, complex, or cross-functional issue that would be best resolved in a short, concentrated time period

For any issue in any of these categories to move forward, these minimums are required:

- A clearly defined issue

- A person responsible for the successful resolution of the issue

- An estimated completion date

This process can be used at the small-group level, or it may be scaled to enterprise-wide use. It can be deployed using easel pads and yellow sticky notes, or a technology solution can be employed.

Sidebar 2

Leader stamina is more important than style in successful change.

It takes stamina to withstand the pressure to return to the comfort zone, and to maintain elevated expectations. This may be the most challenging part of change for the leader. Have tools and a support system in place for those times when your stamina seems to have run out, whether you’re dealing with emotional fatigue or physical fatigue. The support might come from a coach or consultant, a colleague or friend. Self-support might come in the form of a session at the gym or time with a distracting hobby. Whatever works for you, put them in place.

Sidebar 3

Manage your anxiety over resistance

You will recall from the discussion on comfort zones, above, that individuals and groups experience anxiety (among other things) when moving outside their comfort zones. At times that anxiety can be palpable when discussing Lean with a group.

It is times like these that you, as a leader, will need to manage your own anxiety about the resistance you are facing. It should be comforting to know that, if you are experiencing resistance from others, you must be doing something right. Lean without resistance, after all, is not Lean.

When you are facing an anxious group, stay calm and accepting. The following few ideas will help you do that.

- Remember that, as mentioned above, this anxiety is a normal response to significant change.

- Adopt an attitude of curiosity to people’s issues and concerns. The attitude of curiosity has a calming effect on the everyone concerned, including you.6

- Hold appreciative thoughts about those airing their issues and concerns. If you harbor negative judgments—even if they are “true”—it will leak through to your audience, whether you directly express them or not. People pick that up, and those judgments can exacerbate anxiety.

- Breathe.

The following is an example of how to use some of the tools outlined in this article. What follows is a scene where a senior executive is announcing the launch of a Lean initiative to his management team.

Senior exec: We are going to implement Lean in our organization.

[The senior exec goes on to explain some of the details. He then asks if there are any questions or concerns.]

Manager: We don’t have time to do this! We are working flat out as it is. Besides, I don’t think Lean is really going to make us more efficient. We are already pretty lean. And what about the other initiatives? We don’t have the resources to do everything!

[The manager has expressed his concerns. For some reason, he appears emotional as he expresses his concerns. The senior executive, to help ensure he stays calm and curious, takes a deep breath before answering. At this point, the senior executive repeats back what he has heard, and then checks to make sure that he has understood the concerns.]

Senior exec: John, I want to make sure I got what you said. One, you’re saying that you’re working flat out as it is. Two, you don’t think that Lean will make us more efficient; we’re pretty lean already. Three, we have other initiatives competing for the same resources. Did I get that right?

Manager: Yes that’s pretty much it.

[The senior executive makes sure that the issues are written down in a visible place for everyone to see. Capturing the issues in writing where everyone can see them helps prevent people from cycling back to the same issues over and over again. In a meeting room, use a flip chart, an overhead projector, or a computer screen projector. In a virtual meeting, use an online meeting tool so that everyone can see the issues at hand.]

Senior exec: Okay, thanks for bringing those issues up. They’re important and I want to make sure that we address them. So let’s take a look at what we can address right now, and what might need further attention. Looking at number one you’re saying that you’re working flat out as it is. I know that’s a problem, and that’s one of the reasons that we want to implement Lean. Ultimately, we don’t want you to work flat out. You want to work effectively and efficiently, and we want you to be able to work at a sustainable pace. That way we can give the best customer service and we can be more responsive. Now I know at first it might be a bit rough learning new ways of doing things. It might seem like we’re adding more work, especially in the beginning. That happens any time you learn a new skill. After a while, though, Lean will become integrated into the way we do business.

[The senior executive continues in this vein, addressing the issues with reassuring confidence where he can, and reassuring curiosity, where he can’t. For example, a question of priorities came up. In this case, the executive realized that he had not clearly articulated the priorities. Where does Lean fit into the bigger scheme of things? He decided to give himself an action item: meet with his leadership team to clarify and communicate the priorities among the initiatives.]

1 Lean Enterprise Institute, (2007). New Survey: Middle Managers are Biggest Obstacle to Lean Enterprise. http://www.lean.org/WhoWeAre/NewsArticleDocuments/lean_survey_07.pdf

2 Of course, this is a generalization. We’ve all seen small changes that have created a boisterous reaction. What is a big or small change is often a matter of perception.

3 John T. Partington, (1982). Sport in Perspective, p. 27.

4 Other systemic pressures are at play as well.

5 Obviously, there are other structures important in a change effort: a compelling vision, a communication plan, and measurable goals, for example.

6 Curiosity has a calming effect on the self because it (a) shifts one’s frame of mind from emotional to rational, and (b) it focuses one’s attention on the other person(s) and off one’s own anxiety.